Inversion and Incentives

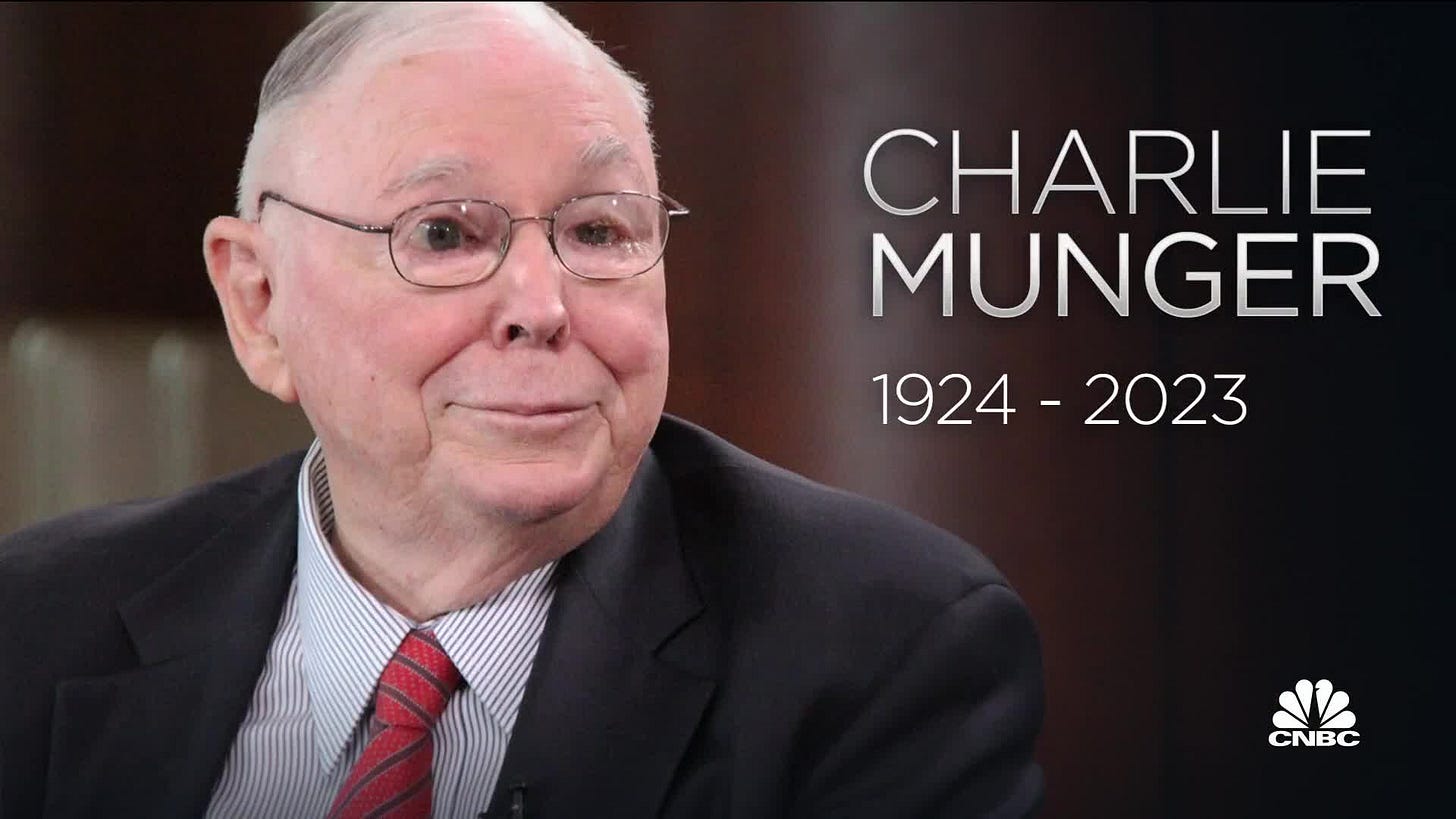

This week marked a year since Charlie Munger passed away.

Munger has had a profound influence on how I approach life. Through his teaching, I came to appreciate how I could make better decisions by developing good mental models about the world.

I’ve found two models in particular to be universal: inversion and incentives.

Inversion: Avoiding Mistakes and Opening Opportunities

Inversion can be understood in two ways.

First, it means starting with the end in mind and working backward to identify the steps needed to achieve a goal.

Second, it means thinking about failure—imagining what could go wrong—and then working to avoid those pitfalls. Both approaches have their place, but I find focusing on avoiding mistakes more powerful.

Why?

Mistakes often have lasting consequences, and what’s wrong tends to stay wrong. By steering clear of bad outcomes, we naturally increase the odds of success. But there’s more to it than that. Success isn’t always a fixed destination. By avoiding failure, we remain flexible, leaving ourselves open to unexpected opportunities and serendipitous gains. This approach reduces downside risks while keeping us exposed to upside potential.

Inversion isn’t about solving problems—it’s about anticipating and avoiding them entirely, which often leads to solutions that might not have been obvious otherwise. For me, it’s a simpler, less stressful way to live.

Incentives: Understanding Human Behavior

Inversion works well for understanding processes and systems, but it’s less useful when it comes to understanding people. Human behavior is much easier to predict when you look at the rewards and penalties that drive it. “Show me the incentive, and I will show you the outcome,” Munger famously said.

When we take the time to understand what motivates people—their incentives—it becomes much easier to anticipate their actions. Whether it’s a business negotiation, managing a team, or even navigating personal relationships, incentives are the key to understanding why people behave the way they do.

A well-designed incentive doesn’t just push people toward a goal—it aligns their behavior with long-term success. By looking at the incentives underlying a situation, we can better understand why people act the way they do and how to create systems that encourage desirable outcomes.

Combining Inversion and Incentives

Inversion and incentives are powerful on their own, but combining them can create a “lollapalooza effect.”

Inversion helps design systems and strategies that avoid harmful outcomes, while incentives help align behavior with goals. Together, they create a feedback loop where good design supports good behavior, and good behavior drives better outcomes.

By designing the right incentives, I can create an environment where the right actions naturally lead to the results I want. That’s not about controlling people, but about creating conditions where success becomes the more likely byproduct.

The Amazon Stories: Inversion and Incentives in Action

Amazon’s success offers one of the clearest examples of how inversion and incentives, when combined, can create transformative results. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder, used both mental models to avoid failure and ensure long-term success by aligning the entire company around one central goal: making the customer happy.

An example is Amazon’s early decision to allow customer reviews on product pages.

At the time, many employees and vendors opposed this idea, arguing that negative reviews would hurt sales. But Bezos approached the problem through inversion, asking: “What frustrates customers about buying products?” One clear answer was misleading information and low-quality products.

By allowing honest reviews—even at the risk of hurting sales—Amazon avoided losing customer trust. Inverting the problem created a solution that didn’t just address a short-term issue but laid the foundation for long-term loyalty and growth.

Another example is the creation of Amazon Prime.

To address a major pain point in online shopping, Bezos asked a simple but powerful question: “What prevents customers from completing transactions?” The answer came back as customers hated paying for shipping and waiting weeks for their orders.

Bezos set out to eliminate these frustrations, leading to the creation of Prime’s two-day shipping, which later evolved into one-day and even same-day delivery

The incentives at Amazon reinforced these decisions.

Bezos’ hyper-focus on making the customer happy aligned the company’s internal goals with this philosophy. Employees were encouraged to focus on doing whatever it took to ensure customer happiness—not just making sales. This shift meant the entire organization prioritized long-term trust over short-term profit, laying the foundation for Amazon’s reputation as the most customer-centric company in the world.

These examples illustrate how inversion and incentives work together. Inversion identifies the critical problems to solve, like misleading product information or shipping frustrations, while well-designed incentives align the company’s actions with the goal of customer happiness. Together, they create a feedback loop where avoiding mistakes and rewarding the right behavior lead to long-term success.

A Framework for Success

Munger’s principles have profoundly shaped the way I think about life and decision-making. Focusing on avoiding mistakes through inversion and understanding behavior through incentives has served as a practical, effective framework for achieving my goals.

The examples of Amazon demonstrate how these principles work in practice. By asking the right questions, avoiding key mistakes, and aligning incentives with core goals, Amazon created systems that serve both the customer and the company. This same approach can be applied to any domain of life—whether personal, professional, or otherwise.

As I reflect on Munger’s legacy, I realize that inversion and incentives aren’t just intellectual tools—they’re a way of looking at and understanding the world around us. Use inversion to avoid mistakes, understand incentives and you will find the world suddenly seems to make a lot more sense.